Rene Recktenwald

HomeBlog

A nice Geometry Puzzle by @Cshearer41

I

I really enjoyed the following puzzle.

All three polygons here are regular. The area of the small hexagon is 5. What’s the area of the large one? pic.twitter.com/kImkQ8Z3Oy

— Catriona Agg (@Cshearer41) March 26, 2021

The setup is very clean, all her puzzles also look gorgeous, and it uses one of my favorite classical geometry theorems. Spoilers ahead!

II

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

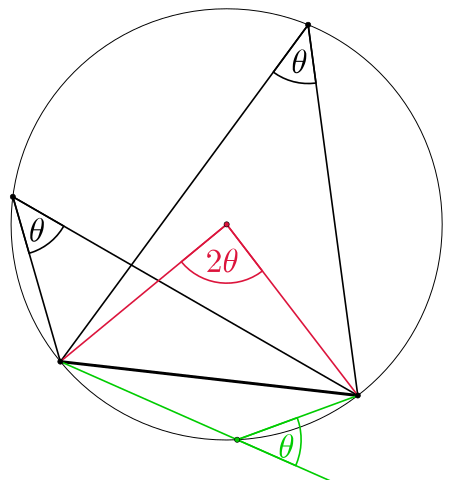

The Inscribed Angle Theorem starts with a circle and a line segment anywhere through this circle, then this segment serves as the base of the triangle, whose third point is the center of the circle. Now if we have any other point on the circle ‘above’ the line, then the angle of the base at this new point is half the angle at the center of the circle. This image from Wikipedia by user Kmhkmh showcases this beautifully.

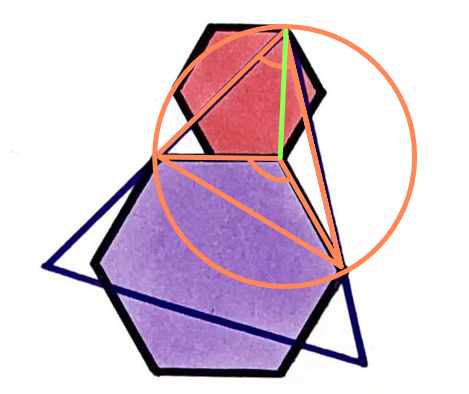

But the nice thing is, that this theorem goes both ways. If we have two triangles, that share a base, such that one of the angles is twice the other one, then we can draw such a circle. We do exactly that for this puzzle. We get the orange circle with the orange triangles.

Since we know that the angle of an equilateral triangle is 60°, while the angle of a regual hexagon is 120°, this is indeed a circle, and the green segment is another radius. I.e. it has the same length as the sides of the big hexagon.

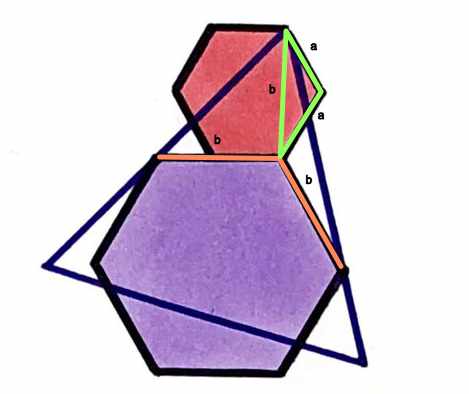

For me, this was the point where I went into calculating; the geometrical reasoning could get me no further. So I used the Law of Cosine, i.e. the equation \(c^2 = a^2+b^2 - 2ab \cos(\gamma)\) as well as the simple fact $\cos(120°)= -\frac12$, on the green triangle

First we get $b^2 = a^2 + a^2 -2a^2\cdot \left(-\frac 12\right) = 3a^2$, which means that the big hexagon has three times the area of the small one, i.e. 15 units.

III

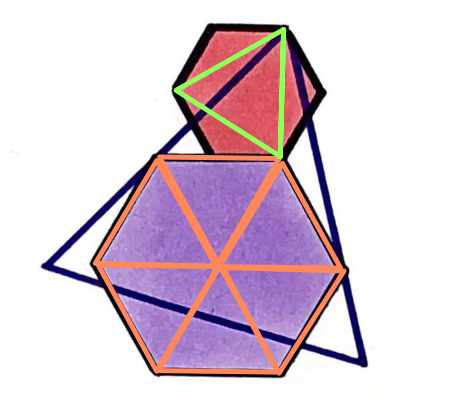

As I said, I couldn’t do the last step geometrically. But Timothy Gowers, one of the most famous mathematicians of our time, could do it. He noticed the following triangles.

It is well-known, and not hard to see, that the green triangle is exactly half of the area of the small hexagon. But we have seen that the green triangle is the same size as the orange ones. There are 6 orange triangles, leading again to an area of 15 units for the big hexagon.

For reference here is the original tweet

A follow-up observation is that one doesn't have to use Pythagoras: an equilateral triangle formed by taking alternate vertices of the small hexagon has half its area, and six copies of it make the big hexagon.

— Timothy Gowers (@wtgowers) March 26, 2021